[ad_1]

Within the first a part of this mini-series on autoregressive circulate fashions, we checked out bijectors in TensorFlow Likelihood (TFP), and noticed find out how to use them for sampling and density estimation. We singled out the affine bijector to display the mechanics of circulate building: We begin from a distribution that’s simple to pattern from, and that permits for easy calculation of its density. Then, we connect some variety of invertible transformations, optimizing for data-likelihood beneath the ultimate remodeled distribution. The effectivity of that (log)probability calculation is the place normalizing flows excel: Loglikelihood beneath the (unknown) goal distribution is obtained as a sum of the density beneath the bottom distribution of the inverse-transformed knowledge plus absolutely the log determinant of the inverse Jacobian.

Now, an affine circulate will seldom be highly effective sufficient to mannequin nonlinear, complicated transformations. In constrast, autoregressive fashions have proven substantive success in density estimation in addition to pattern era. Mixed with extra concerned architectures, characteristic engineering, and intensive compute, the idea of autoregressivity has powered – and is powering – state-of-the-art architectures in areas similar to picture, speech and video modeling.

This publish might be involved with the constructing blocks of autoregressive flows in TFP. Whereas we gained’t precisely be constructing state-of-the-art fashions, we’ll attempt to perceive and play with some main elements, hopefully enabling the reader to do her personal experiments on her personal knowledge.

This publish has three elements: First, we’ll have a look at autoregressivity and its implementation in TFP. Then, we attempt to (roughly) reproduce one of many experiments within the “MAF paper” (Masked Autoregressive Flows for Distribution Estimation (Papamakarios, Pavlakou, and Murray 2017)) – primarily a proof of idea. Lastly, for the third time on this weblog, we come again to the duty of analysing audio knowledge, with blended outcomes.

Autoregressivity and masking

In distribution estimation, autoregressivity enters the scene by way of the chain rule of chance that decomposes a joint density right into a product of conditional densities:

[

p(mathbf{x}) = prod_{i}p(mathbf{x}_i|mathbf{x}_{1:i−1})

]

In follow, which means autoregressive fashions must impose an order on the variables – an order which could or won’t “make sense.” Approaches right here embody selecting orderings at random and/or utilizing completely different orderings for every layer.

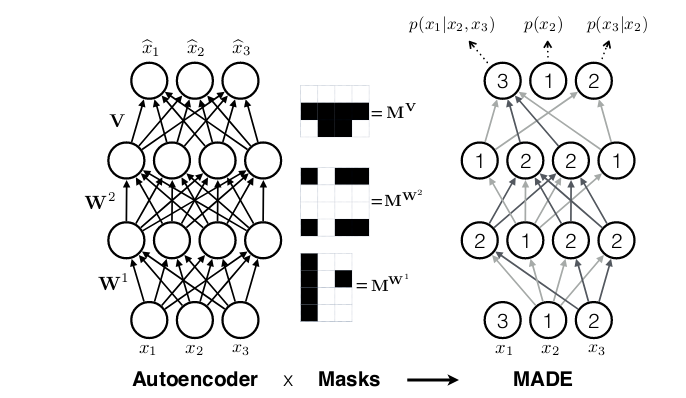

Whereas in recurrent neural networks, autoregressivity is conserved as a result of recurrence relation inherent in state updating, it isn’t clear a priori how autoregressivity is to be achieved in a densely related structure. A computationally environment friendly resolution was proposed in MADE: Masked Autoencoder for Distribution Estimation(Germain et al. 2015): Ranging from a densely related layer, masks out all connections that shouldn’t be allowed, i.e., all connections from enter characteristic (i) to mentioned layer’s activations (1 … i-1). Or expressed otherwise, activation (i) could also be related to enter options (1 … i-1) solely. Then when including extra layers, care should be taken to make sure that all required connections are masked in order that on the finish, output (i) will solely ever have seen inputs (1 … i-1).

Thus masked autoregressive flows are a fusion of two main approaches – autoregressive fashions (which needn’t be flows) and flows (which needn’t be autoregressive). In TFP these are offered by MaskedAutoregressiveFlow, for use as a bijector in a TransformedDistribution.

Whereas the documentation reveals find out how to use this bijector, the step from theoretical understanding to coding a “black field” could appear extensive. In the event you’re something just like the writer, right here you may really feel the urge to “look beneath the hood” and confirm that issues actually are the way in which you’re assuming. So let’s give in to curiosity and permit ourselves a bit of escapade into the supply code.

Peeking forward, that is how we’ll assemble a masked autoregressive circulate in TFP (once more utilizing the nonetheless new-ish R bindings offered by tfprobability):

library(tfprobability)

maf <- tfb_masked_autoregressive_flow(

shift_and_log_scale_fn = tfb_masked_autoregressive_default_template(

hidden_layers = record(num_hidden, num_hidden),

activation = tf$nn$tanh)

)Pulling aside the related entities right here, tfb_masked_autoregressive_flow is a bijector, with the standard strategies tfb_forward(), tfb_inverse(), tfb_forward_log_det_jacobian() and tfb_inverse_log_det_jacobian().

The default shift_and_log_scale_fn, tfb_masked_autoregressive_default_template, constructs a bit of neural community of its personal, with a configurable variety of hidden items per layer, a configurable activation operate and optionally, different configurable parameters to be handed to the underlying dense layers. It’s these dense layers that must respect the autoregressive property. Can we check out how that is finished? Sure we will, offered we’re not afraid of a bit of Python.

masked_autoregressive_default_template (now leaving out the tfb_ as we’ve entered Python-land) makes use of masked_dense to do what you’d suppose a thus-named operate is likely to be doing: assemble a dense layer that has a part of the load matrix masked out. How? We’ll see after a couple of Python setup statements.

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

import tensorflow_probability as tfp

tfd = tfp.distributions

tfb = tfp.bijectors

tf.enable_eager_execution()The next code snippets are taken from masked_dense (in its present type on grasp), and when doable, simplified for higher readability, accommodating simply the specifics of the chosen instance – a toy matrix of form 2×3:

# assemble some toy enter knowledge (this line clearly not from the unique code)

inputs = tf.fixed(np.arange(1.,7), form = (2, 3))

# (partly) decide form of masks from form of enter

input_depth = tf.compat.dimension_value(inputs.form.with_rank_at_least(1)[-1])

num_blocks = input_depth

num_blocks # 3Our toy layer ought to have 4 items:

The masks is initialized to all zeros. Contemplating it will likely be used to elementwise multiply the load matrix, we’re a bit shocked at its form (shouldn’t or not it’s the opposite manner spherical?). No worries; all will prove right ultimately.

masks = np.zeros([units, input_depth], dtype=tf.float32.as_numpy_dtype())

masksarray([[0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0.]], dtype=float32)Now to “whitelist” the allowed connections, we’ve got to fill in ones at any time when info circulate is allowed by the autoregressive property:

def _gen_slices(num_blocks, n_in, n_out):

slices = []

col = 0

d_in = n_in // num_blocks

d_out = n_out // num_blocks

row = d_out

for _ in vary(num_blocks):

row_slice = slice(row, None)

col_slice = slice(col, col + d_in)

slices.append([row_slice, col_slice])

col += d_in

row += d_out

return slices

slices = _gen_slices(num_blocks, input_depth, items)

for [row_slice, col_slice] in slices:

masks[row_slice, col_slice] = 1

masksarray([[0., 0., 0.],

[1., 0., 0.],

[1., 1., 0.],

[1., 1., 1.]], dtype=float32)Once more, does this look mirror-inverted? A transpose fixes form and logic each:

array([[0., 1., 1., 1.],

[0., 0., 1., 1.],

[0., 0., 0., 1.]], dtype=float32)Now that we’ve got the masks, we will create the layer (curiously, as of this writing not (but?) a tf.keras layer):

layer = tf.compat.v1.layers.Dense(

items,

kernel_initializer=masked_initializer, # 1

kernel_constraint=lambda x: masks * x # 2

)Right here we see masking occurring in two methods. For one, the load initializer is masked:

kernel_initializer = tf.compat.v1.glorot_normal_initializer()

def masked_initializer(form, dtype=None, partition_info=None):

return masks * kernel_initializer(form, dtype, partition_info)And secondly, a kernel constraint makes positive that after optimization, the relative items are zeroed out once more:

kernel_constraint=lambda x: masks * x Only for enjoyable, let’s apply the layer to our toy enter:

<tf.Tensor: id=30, form=(2, 4), dtype=float64, numpy=

array([[ 0. , -0.7489589 , -0.43329933, 1.42710014],

[ 0. , -2.9958356 , -1.71647246, 1.09258015]])>Zeroes the place anticipated. And double-checking on the load matrix…

<tf.Variable 'dense/kernel:0' form=(3, 4) dtype=float64, numpy=

array([[ 0. , -0.7489589 , -0.42214942, -0.6473454 ],

[-0. , 0. , -0.00557496, -0.46692933],

[-0. , -0. , -0. , 1.00276807]])>Good. Now hopefully after this little deep dive, issues have change into a bit extra concrete. After all in a much bigger mannequin, the autoregressive property needs to be conserved between layers as effectively.

On to the second matter, utility of MAF to a real-world dataset.

Masked Autoregressive Stream

The MAF paper(Papamakarios, Pavlakou, and Murray 2017) utilized masked autoregressive flows (in addition to single-layer-MADE(Germain et al. 2015) and Actual NVP (Dinh, Sohl-Dickstein, and Bengio 2016)) to plenty of datasets, together with MNIST, CIFAR-10 and several other datasets from the UCI Machine Studying Repository.

We choose one of many UCI datasets: Gasoline sensors for house exercise monitoring. On this dataset, the MAF authors obtained one of the best outcomes utilizing a MAF with 10 flows, so that is what we’ll attempt.

Gathering info from the paper, we all know that

- knowledge was included from the file ethylene_CO.txt solely;

- discrete columns had been eradicated, in addition to all columns with correlations > .98; and

- the remaining 8 columns had been standardised (z-transformed).

Relating to the neural community structure, we collect that

- every of the ten MAF layers was adopted by a batchnorm;

- as to characteristic order, the primary MAF layer used the variable order that got here with the dataset; then each consecutive layer reversed it;

- particularly for this dataset and versus all different UCI datasets, tanh was used for activation as an alternative of relu;

- the Adam optimizer was used, with a studying fee of 1e-4;

- there have been two hidden layers for every MAF, with 100 items every;

- coaching went on till no enchancment occurred for 30 consecutive epochs on the validation set; and

- the bottom distribution was a multivariate Gaussian.

That is all helpful info for our try to estimate this dataset, however the important bit is that this. In case you knew the dataset already, you may need been questioning how the authors would take care of the dimensionality of the information: It’s a time sequence, and the MADE structure explored above introduces autoregressivity between options, not time steps. So how is the extra temporal autoregressivity to be dealt with? The reply is: The time dimension is actually eliminated. Within the authors’ phrases,

[…] it’s a time sequence however was handled as if every instance had been an i.i.d. pattern from the marginal distribution.

This undoubtedly is helpful info for our current modeling try, nevertheless it additionally tells us one thing else: We’d must look past MADE layers for precise time sequence modeling.

Now although let’s have a look at this instance of utilizing MAF for multivariate modeling, with no time or spatial dimension to be taken under consideration.

Following the hints the authors gave us, that is what we do.

Observations: 4,208,261

Variables: 19

$ X1 <dbl> 0.00, 0.01, 0.01, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06, 0.07, 0.07, 0.09,...

$ X2 <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,...

$ X3 <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,...

$ X4 <dbl> -50.85, -49.40, -40.04, -47.14, -33.58, -48.59, -48.27, -47.14,...

$ X5 <dbl> -1.95, -5.53, -16.09, -10.57, -20.79, -11.54, -9.11, -4.56,...

$ X6 <dbl> -41.82, -42.78, -27.59, -32.28, -33.25, -36.16, -31.31, -16.57,...

$ X7 <dbl> 1.30, 0.49, 0.00, 4.40, 6.03, 6.03, 5.37, 4.40, 23.98, 2.77,...

$ X8 <dbl> -4.07, 3.58, -7.16, -11.22, 3.42, 0.33, -7.97, -2.28, -2.12,...

$ X9 <dbl> -28.73, -34.55, -42.14, -37.94, -34.22, -29.05, -30.34, -24.35,...

$ X10 <dbl> -13.49, -9.59, -12.52, -7.16, -14.46, -16.74, -8.62, -13.17,...

$ X11 <dbl> -3.25, 5.37, -5.86, -1.14, 8.31, -1.14, 7.00, -6.34, -0.81,...

$ X12 <dbl> 55139.95, 54395.77, 53960.02, 53047.71, 52700.28, 51910.52,...

$ X13 <dbl> 50669.50, 50046.91, 49299.30, 48907.00, 48330.96, 47609.00,...

$ X14 <dbl> 9626.26, 9433.20, 9324.40, 9170.64, 9073.64, 8982.88, 8860.51,...

$ X15 <dbl> 9762.62, 9591.21, 9449.81, 9305.58, 9163.47, 9021.08, 8966.48,...

$ X16 <dbl> 24544.02, 24137.13, 23628.90, 23101.66, 22689.54, 22159.12,...

$ X17 <dbl> 21420.68, 20930.33, 20504.94, 20101.42, 19694.07, 19332.57,...

$ X18 <dbl> 7650.61, 7498.79, 7369.67, 7285.13, 7156.74, 7067.61, 6976.13,...

$ X19 <dbl> 6928.42, 6800.66, 6697.47, 6578.52, 6468.32, 6385.31, 6300.97,...# A tibble: 4,208,261 x 8

X4 X5 X8 X9 X13 X16 X17 X18

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 -50.8 -1.95 -4.07 -28.7 50670. 24544. 21421. 7651.

2 -49.4 -5.53 3.58 -34.6 50047. 24137. 20930. 7499.

3 -40.0 -16.1 -7.16 -42.1 49299. 23629. 20505. 7370.

4 -47.1 -10.6 -11.2 -37.9 48907 23102. 20101. 7285.

5 -33.6 -20.8 3.42 -34.2 48331. 22690. 19694. 7157.

6 -48.6 -11.5 0.33 -29.0 47609 22159. 19333. 7068.

7 -48.3 -9.11 -7.97 -30.3 47047. 21932. 19028. 6976.

8 -47.1 -4.56 -2.28 -24.4 46758. 21504. 18780. 6900.

9 -42.3 -2.77 -2.12 -27.6 46197. 21125. 18439. 6827.

10 -44.6 3.58 -0.65 -35.5 45652. 20836. 18209. 6790.

# … with 4,208,251 extra rowsNow arrange the information era course of:

# train-test break up

n_rows <- nrow(df2) # 4208261

train_ids <- pattern(1:n_rows, 0.5 * n_rows)

x_train <- df2[train_ids, ]

x_test <- df2[-train_ids, ]

# create datasets

batch_size <- 100

train_dataset <- tf$solid(x_train, tf$float32) %>%

tensor_slices_dataset %>%

dataset_batch(batch_size)

test_dataset <- tf$solid(x_test, tf$float32) %>%

tensor_slices_dataset %>%

dataset_batch(nrow(x_test))To assemble the circulate, the very first thing wanted is the bottom distribution.

Now for the circulate, by default constructed with batchnorm and permutation of characteristic order.

num_hidden <- 100

dim <- ncol(df2)

use_batchnorm <- TRUE

use_permute <- TRUE

num_mafs <-10

num_layers <- 3 * num_mafs

bijectors <- vector(mode = "record", size = num_layers)

for (i in seq(1, num_layers, by = 3)) {

maf <- tfb_masked_autoregressive_flow(

shift_and_log_scale_fn = tfb_masked_autoregressive_default_template(

hidden_layers = record(num_hidden, num_hidden),

activation = tf$nn$tanh))

bijectors[[i]] <- maf

if (use_batchnorm)

bijectors[[i + 1]] <- tfb_batch_normalization()

if (use_permute)

bijectors[[i + 2]] <- tfb_permute((ncol(df2) - 1):0)

}

if (use_permute) bijectors <- bijectors[-num_layers]

circulate <- bijectors %>%

discard(is.null) %>%

# tfb_chain expects arguments in reverse order of utility

rev() %>%

tfb_chain()

target_dist <- tfd_transformed_distribution(

distribution = base_dist,

bijector = circulate

)And configuring the optimizer:

optimizer <- tf$practice$AdamOptimizer(1e-4)Beneath that isotropic Gaussian we selected as a base distribution, how probably are the information?

base_loglik <- base_dist %>%

tfd_log_prob(x_train) %>%

tf$reduce_mean()

base_loglik %>% as.numeric() # -11.33871

base_loglik_test <- base_dist %>%

tfd_log_prob(x_test) %>%

tf$reduce_mean()

base_loglik_test %>% as.numeric() # -11.36431And, simply as a fast sanity examine: What’s the loglikelihood of the information beneath the remodeled distribution earlier than any coaching?

target_loglik_pre <-

target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(x_train) %>% tf$reduce_mean()

target_loglik_pre %>% as.numeric() # -11.22097

target_loglik_pre_test <-

target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(x_test) %>% tf$reduce_mean()

target_loglik_pre_test %>% as.numeric() # -11.36431The values match – good. Right here now’s the coaching loop. Being impatient, we already maintain checking the loglikelihood on the (full) take a look at set to see if we’re making any progress.

n_epochs <- 10

for (i in 1:n_epochs) {

agg_loglik <- 0

num_batches <- 0

iter <- make_iterator_one_shot(train_dataset)

until_out_of_range({

batch <- iterator_get_next(iter)

loss <-

operate()

- tf$reduce_mean(target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(batch))

optimizer$reduce(loss)

loglik <- tf$reduce_mean(target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(batch))

agg_loglik <- agg_loglik + loglik

num_batches <- num_batches + 1

test_iter <- make_iterator_one_shot(test_dataset)

test_batch <- iterator_get_next(test_iter)

loglik_test_current <- target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(test_batch) %>% tf$reduce_mean()

if (num_batches %% 100 == 1)

cat(

"Epoch ",

i,

": ",

"Batch ",

num_batches,

": ",

(agg_loglik %>% as.numeric()) / num_batches,

" --- take a look at: ",

loglik_test_current %>% as.numeric(),

"n"

)

})

}With each coaching and take a look at units amounting to over 2 million data every, we didn’t have the endurance to run this mannequin till no enchancment occurred for 30 consecutive epochs on the validation set (just like the authors did). Nonetheless, the image we get from one full epoch’s run is fairly clear: The setup appears to work fairly okay.

Epoch 1 : Batch 1: -8.212026 --- take a look at: -10.09264

Epoch 1 : Batch 1001: 2.222953 --- take a look at: 1.894102

Epoch 1 : Batch 2001: 2.810996 --- take a look at: 2.147804

Epoch 1 : Batch 3001: 3.136733 --- take a look at: 3.673271

Epoch 1 : Batch 4001: 3.335549 --- take a look at: 4.298822

Epoch 1 : Batch 5001: 3.474280 --- take a look at: 4.502975

Epoch 1 : Batch 6001: 3.606634 --- take a look at: 4.612468

Epoch 1 : Batch 7001: 3.695355 --- take a look at: 4.146113

Epoch 1 : Batch 8001: 3.767195 --- take a look at: 3.770533

Epoch 1 : Batch 9001: 3.837641 --- take a look at: 4.819314

Epoch 1 : Batch 10001: 3.908756 --- take a look at: 4.909763

Epoch 1 : Batch 11001: 3.972645 --- take a look at: 3.234356

Epoch 1 : Batch 12001: 4.020613 --- take a look at: 5.064850

Epoch 1 : Batch 13001: 4.067531 --- take a look at: 4.916662

Epoch 1 : Batch 14001: 4.108388 --- take a look at: 4.857317

Epoch 1 : Batch 15001: 4.147848 --- take a look at: 5.146242

Epoch 1 : Batch 16001: 4.177426 --- take a look at: 4.929565

Epoch 1 : Batch 17001: 4.209732 --- take a look at: 4.840716

Epoch 1 : Batch 18001: 4.239204 --- take a look at: 5.222693

Epoch 1 : Batch 19001: 4.264639 --- take a look at: 5.279918

Epoch 1 : Batch 20001: 4.291542 --- take a look at: 5.29119

Epoch 1 : Batch 21001: 4.314462 --- take a look at: 4.872157

Epoch 2 : Batch 1: 5.212013 --- take a look at: 4.969406 With these coaching outcomes, we regard the proof of idea as mainly profitable. Nonetheless, from our experiments we additionally must say that the selection of hyperparameters appears to matter a lot. For instance, use of the relu activation operate as an alternative of tanh resulted within the community mainly studying nothing. (As per the authors, relu labored high quality on different datasets that had been z-transformed in simply the identical manner.)

Batch normalization right here was compulsory – and this may go for flows on the whole. The permutation bijectors, however, didn’t make a lot of a distinction on this dataset. General the impression is that for flows, we would both want a “bag of methods” (like is usually mentioned about GANs), or extra concerned architectures (see “Outlook” beneath).

Lastly, we wind up with an experiment, coming again to our favourite audio knowledge, already featured in two posts: Easy Audio Classification with Keras and Audio classification with Keras: Trying nearer on the non-deep studying elements.

Analysing audio knowledge with MAF

The dataset in query consists of recordings of 30 phrases, pronounced by plenty of completely different audio system. In these earlier posts, a convnet was educated to map spectrograms to these 30 lessons. Now as an alternative we need to attempt one thing completely different: Prepare an MAF on one of many lessons – the phrase “zero,” say – and see if we will use the educated community to mark “non-zero” phrases as much less probably: carry out anomaly detection, in a manner. Spoiler alert: The outcomes weren’t too encouraging, and if you’re concerned with a process like this, you may need to take into account a distinct structure (once more, see “Outlook” beneath).

Nonetheless, we rapidly relate what was finished, as this process is a pleasant instance of dealing with knowledge the place options fluctuate over a couple of axis.

Preprocessing begins as within the aforementioned earlier posts. Right here although, we explicitly use keen execution, and should typically hard-code recognized values to maintain the code snippets quick.

library(tensorflow)

library(tfprobability)

tfe_enable_eager_execution(device_policy = "silent")

library(tfdatasets)

library(dplyr)

library(readr)

library(purrr)

library(caret)

library(stringr)

# make decode_wav() run with the present launch 1.13.1 in addition to with the present grasp department

decode_wav <- operate() if (reticulate::py_has_attr(tf, "audio")) tf$audio$decode_wav

else tf$contrib$framework$python$ops$audio_ops$decode_wav

# similar for stft()

stft <- operate() if (reticulate::py_has_attr(tf, "sign")) tf$sign$stft else tf$spectral$stft

information <- fs::dir_ls(path = "audio/data_1/speech_commands_v0.01/", # exchange by yours

recursive = TRUE,

glob = "*.wav")

information <- information[!str_detect(files, "background_noise")]

df <- tibble(

fname = information,

class = fname %>%

str_extract("v0.01/.*/") %>%

str_replace_all("v0.01/", "") %>%

str_replace_all("/", "")

)We practice the MAF on pronunciations of the phrase “zero.”

Following the strategy detailed in Audio classification with Keras: Trying nearer on the non-deep studying elements, we’d like to coach the community on spectrograms as an alternative of the uncooked time area knowledge.

Utilizing the identical settings for frame_length and frame_step of the Quick Time period Fourier Rework as in that publish, we’d arrive at knowledge formed variety of frames x variety of FFT coefficients. To make this work with the masked_dense() employed in tfb_masked_autoregressive_flow(), the information would then must be flattened, yielding a powerful 25186 options within the joint distribution.

With the structure outlined as above within the GAS instance, this result in the community not making a lot progress. Neither did leaving the information in time area type, with 16000 options within the joint distribution. Thus, we determined to work with the FFT coefficients computed over the whole window as an alternative, leading to 257 joint options.

batch_size <- 100

sampling_rate <- 16000L

data_generator <- operate(df,

batch_size) {

ds <- tensor_slices_dataset(df)

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_map(operate(obs) {

wav <-

decode_wav()(tf$read_file(tf$reshape(obs$fname, record())))

samples <- wav$audio[ ,1]

# some wave information have fewer than 16000 samples

padding <- record(record(0L, sampling_rate - tf$form(samples)[1]))

padded <- tf$pad(samples, padding)

stft_out <- stft()(padded, 16000L, 1L, 512L)

magnitude_spectrograms <- tf$abs(stft_out) %>% tf$squeeze()

})

ds %>% dataset_batch(batch_size)

}

ds_train <- data_generator(df_train, batch_size)

batch <- ds_train %>%

make_iterator_one_shot() %>%

iterator_get_next()

dim(batch) # 100 x 257Coaching then proceeded as on the GAS dataset.

# outline MAF

base_dist <-

tfd_multivariate_normal_diag(loc = rep(0, dim(batch)[2]))

num_hidden <- 512

use_batchnorm <- TRUE

use_permute <- TRUE

num_mafs <- 10

num_layers <- 3 * num_mafs

# retailer bijectors in a listing

bijectors <- vector(mode = "record", size = num_layers)

# fill record, optionally including batchnorm and permute bijectors

for (i in seq(1, num_layers, by = 3)) {

maf <- tfb_masked_autoregressive_flow(

shift_and_log_scale_fn = tfb_masked_autoregressive_default_template(

hidden_layers = record(num_hidden, num_hidden),

activation = tf$nn$tanh,

))

bijectors[[i]] <- maf

if (use_batchnorm)

bijectors[[i + 1]] <- tfb_batch_normalization()

if (use_permute)

bijectors[[i + 2]] <- tfb_permute((dim(batch)[2] - 1):0)

}

if (use_permute) bijectors <- bijectors[-num_layers]

circulate <- bijectors %>%

# probably clear out empty parts (if no batchnorm or no permute)

discard(is.null) %>%

rev() %>%

tfb_chain()

target_dist <- tfd_transformed_distribution(distribution = base_dist,

bijector = circulate)

optimizer <- tf$practice$AdamOptimizer(1e-3)

# practice MAF

n_epochs <- 100

for (i in 1:n_epochs) {

agg_loglik <- 0

num_batches <- 0

iter <- make_iterator_one_shot(ds_train)

until_out_of_range({

batch <- iterator_get_next(iter)

loss <-

operate()

- tf$reduce_mean(target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(batch))

optimizer$reduce(loss)

loglik <- tf$reduce_mean(target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(batch))

agg_loglik <- agg_loglik + loglik

num_batches <- num_batches + 1

loglik_test_current <-

target_dist %>% tfd_log_prob(ds_test) %>% tf$reduce_mean()

if (num_batches %% 20 == 1)

cat(

"Epoch ",

i,

": ",

"Batch ",

num_batches,

": ",

((agg_loglik %>% as.numeric()) / num_batches) %>% spherical(1),

" --- take a look at: ",

loglik_test_current %>% as.numeric() %>% spherical(1),

"n"

)

})

}Throughout coaching, we additionally monitored loglikelihoods on three completely different lessons, cat, chicken and wow. Listed here are the loglikelihoods from the primary 10 epochs. “Batch” refers back to the present coaching batch (first batch within the epoch), all different values refer to finish datasets (the whole take a look at set and the three units chosen for comparability).

epoch | batch | take a look at | "cat" | "chicken" | "wow" |

--------|----------|----------|----------|-----------|----------|

1 | 1443.5 | 1455.2 | 1398.8 | 1434.2 | 1546.0 |

2 | 1935.0 | 2027.0 | 1941.2 | 1952.3 | 2008.1 |

3 | 2004.9 | 2073.1 | 2003.5 | 2000.2 | 2072.1 |

4 | 2063.5 | 2131.7 | 2056.0 | 2061.0 | 2116.4 |

5 | 2120.5 | 2172.6 | 2096.2 | 2085.6 | 2150.1 |

6 | 2151.3 | 2206.4 | 2127.5 | 2110.2 | 2180.6 |

7 | 2174.4 | 2224.8 | 2142.9 | 2163.2 | 2195.8 |

8 | 2203.2 | 2250.8 | 2172.0 | 2061.0 | 2221.8 |

9 | 2224.6 | 2270.2 | 2186.6 | 2193.7 | 2241.8 |

10 | 2236.4 | 2274.3 | 2191.4 | 2199.7 | 2243.8 | Whereas this doesn’t look too unhealthy, a whole comparability towards all twenty-nine non-target lessons had “zero” outperformed by seven different lessons, with the remaining twenty-two decrease in loglikelihood. We don’t have a mannequin for anomaly detection, as but.

Outlook

As already alluded to a number of occasions, for knowledge with temporal and/or spatial orderings extra developed architectures might show helpful. The very profitable PixelCNN household relies on masked convolutions, with newer developments bringing additional refinements (e.g. Gated PixelCNN (Oord et al. 2016), PixelCNN++ (Salimans et al. 2017). Consideration, too, could also be masked and thus rendered autoregressive, as employed within the hybrid PixelSNAIL (Chen et al. 2017) and the – not surprisingly given its title – transformer-based ImageTransformer (Parmar et al. 2018).

To conclude, – whereas this publish was within the intersection of flows and autoregressivity – and final not least the use therein of TFP bijectors – an upcoming one may dive deeper into autoregressive fashions particularly… and who is aware of, maybe come again to the audio knowledge for a fourth time.

[ad_2]